I mentioned earlier that the First of the Nine-Nines—the Nine-Nines being nine periods of nine days each, each period characterized by a certain type of winter weather—started on the day of the Winter Solstice, which occurred here in Mongolia on December 21, according to the Gregorian Calendar. The Second of the Nine Nines begins today, December 30. Known as Khorz Arkhi Khöldönö, this is the time when twice-distilled homemade Mongolian arkhi (vodka) freezes. As you will recall, the first of the Nine-Nines was the time when regular, or once distilled, arkhi freezes. As this indicates, the second period should be colder than the first, since twice distilled arkhi obviously has a much higher alcohol content. This morning at 8:30 it was a relatively balmy Minus 22°F /-30º C, however, and it is supposed to get up to minus 4º F / -20º C today, so we seem to be having a bit of a warm spell. The Third Nine-Nine starts on January 8.

Saturday, December 29, 2012

Mongolia | Second Nine Nine | Khorz Arkhi Khöldönö

I mentioned earlier that the First of the Nine-Nines—the Nine-Nines being nine periods of nine days each, each period characterized by a certain type of winter weather—started on the day of the Winter Solstice, which occurred here in Mongolia on December 21, according to the Gregorian Calendar. The Second of the Nine Nines begins today, December 30. Known as Khorz Arkhi Khöldönö, this is the time when twice-distilled homemade Mongolian arkhi (vodka) freezes. As you will recall, the first of the Nine-Nines was the time when regular, or once distilled, arkhi freezes. As this indicates, the second period should be colder than the first, since twice distilled arkhi obviously has a much higher alcohol content. This morning at 8:30 it was a relatively balmy Minus 22°F /-30º C, however, and it is supposed to get up to minus 4º F / -20º C today, so we seem to be having a bit of a warm spell. The Third Nine-Nine starts on January 8.

Thursday, December 27, 2012

Uzbekistan | Bukhara | Arab Invasion

By the end of the sixth century Bukhara Was Flourishing, but dangers lurked just beyond the horizon. It was probably around this time that the Sogdians constructed the Kanpirak, or “Old Woman”, the 150 or-more-long wall which surrounded most of the Bukhara Oasis and served as a bulwark against the hostile Turkish nomads who inhabited the deserts and steppes to the north. The invaders who would bring down Sogdiana and forever change the way of life in the Land Beyond the River came not from the north, however, but from the south, in form of Arabs who came proclaiming the new religion of Islam.

The Prophet Muhammed died in June of 632 a.d. Abu Bakr, his father-in-law and senior companion, assumed leadership of the Prophet’s followers and became the first of the Four Rightly Guided Caliphs. The Caliph and his successors had a simple mandate: the spread of Islam, by military conquest if necessary, to the far corners of the world. In the spring of 633 Arab General Khalid ibn Walid, acting under orders from Abu Bakr, invaded Mesopotamia (current-day Iraq), then part of the vast Sassanian Empire stretching from near the shores of the Mediterranean to the Indus River. The incursion faltered after the death of Abu Bakr in 1634, but under this successor the second Caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab the invasion continued and in September of 636 the Arabs defeated a huge Sassanian army in a three-day battle at the small town of Qadisiyyah, just east of Kufa and about one hundred miles southeast of Baghdad. Not long after the Sassanian imperial capital of Ctesiphon, eighteen miles southeast of Baghdad, surrendered without a fight, and the Sassanian emperor Yazdgird III along with his family and entourage fled eastward, taking refuge behind the natural border of the Zagros Mountains, which separated Mesopotamia from the Iranian Plateau. In 642 Caliph Umar ordered his Muslim armies over the Zagros Mountains into the Sassanian heartland. Although vastly outnumbered the Arabs soon scored a stunning victory at Nahāvand, about forty miles south of Hamadan in what is now Iran. The Battle of Nahāvand was a death blow to the Sassanians. According to Islamic historian al-Tabari (838–923), “from that day on, there was no further unity among them [the Persians] and the people of the individual provinces fought their own enemies on their own territory.”

Yazdgird III, accompanied by thousands of relatives, hangers-on, and a small contingent of still-loyal troops fled farther eastward to Khorasan, passing through Nishapur and finally reached the then-already ancient city of Merv (fifty-five miles northwest of Mary in current-day Turkmenistan). Envoys which he had dispatched to Sogdians and Turk tribesmen north of the Amu Darya and to the Tang Dynasty in China seeking aid to renew the battle against the Arabs came away empty-handed. Abandoned by the remainder of his troops, he again took flight and ended up hiding in the flour mill of a Christian miller on the banks of the Mugrab River south of Merv. In 651 he was assassinated, perhaps by the miller himself. After 427 years the Sassanian Empire was finally extinguished.

The same year Arab armies occupied Merv, 120 miles south of the Amu Darya, and Herat, on the western edge of Khorasan, and the following year Balkh, in Tokharistan (current day northern Afghanistan), just thirty-five miles south of the Amu Darya. The Arabs invaders, now colonists, set up a governorship in Merv and used it as a base for further military forays to the north. Small raiding parties operating out of Merv may have penetrated Khorezm on the lower Amu Darya in the 660s, but the first substantial campaign north of the Amu Darya took place in 673, when the governor of Khorasan Ubaidullah b. Ziyad led a force across the river to Bukhara. The Arabs were now in Transoxiania, or as they called it, Mawarannahr, literally “that which is beyond the river.”

At this time Bukhara was still a Sogdian city and according to some accounts it was ruled by a khatun, or queen, who was the mother of the young Tugshada, the nominal Bukhar Khudat (ruler of Bukhara). She negotiated a truce with the Arabs and after paying them tribute of a million dirhams and 4,000 slaves they retreated back south of the river.

For the next thirty years the Arabs continued to raid Bukhara and other cities in Mawarannahr and Khorezm but after demanding tribute from the local rulers, plundering the countryside, and enslaving Sogdians they continued to return to their bases south of the Amu Darya. In 705 al-Walid I ibn Abd al-Malik became the new Umayyads Caliph in Damascus, and under his reign the actual conquest of Mawarannahr began. Qutaiba b. Muslim, newly appointed governor of Khorasan, led an Arab army across the Amu Darya at Amul and in 706 attacked the city of Paikend at the very southern edge of the Bukhara Oasis.

After a two-month siege the city fell. Qutaiba left a small garrison of troops and returned to Merv, but soon after his departure the Arab troops were expelled from the city. Qutaiba returned and wrecked horrific revenge, putting the fighting men to death, enslaving the women, and completely plundering the city. Enormous amounts of booty was seized, including armor and weapons the quality of which amazed the Arabs. The message to the rest of the Zerafshan Valley was clear; submit and pay tribute or face annihilation.

With the destruction of Paikend the way was clear to Bukhara, thirty-one miles to the northeast. Assaults on Bukhara in 707 and 708 failed, but 709 Bukhara and several other cities in Mawarannahr finally surrendered to Qutaiba. From the Bukharans he collected tribute of 200,000 dirhams for the Caliph back in Damascus and 20,000 for the governor of Khorasan. A garrison was stationed in the city and every homeowner was made to house and presumably feed Arab troops.

In 712 Qutaiba built the first mosque in Bukhara on the former site of a temple in the Ark, marking the introduction of Islam into the city. The temple may be been Zoroastrian, or possible even Buddhist. Apparently the local people did not immediately accept Islam, since, according to tenth-century historian of Bukhara Narshakhi, Qutaiba had proclaimed, “Whoever is present at the Friday prayer, I will give two dirhams.” The Quran had to be read in Sogdian, since none of the local people understood Arabic.

For the next hundred years Arabs maintained tenuous control of Bukhara and other cities in Mawarannahr. Revolts by the indigenous Sogdians were frequent, and in 729 they succeeded in expelling the Arabs from Bukhara altogether, although the city was taken a few months later. In the 740s the Abbasids (descendants of Abbas, uncle of the Prophet Muhammad) attempted to seize control of the Islamic geo-sphere from the Umayyads. Their lieutenant in Khorasan and Mawarannahr, Abu Muslim, defeated the Umayyads in 747–748, and local people, believing they were being liberated, flocked to his banner. They soon realized, however, that the Abbasids, who finally seized the Caliphate in 750, were no better than the Umayyads. Revolts and rebellions against the ruling Arabs continued.

Uzbekistan | Bukhara | Arab Invasion

By the end of the sixth century Bukhara Was Flourishing, but dangers lurked just beyond the horizon. It was probably around this time that the Sogdians constructed the Kanpirak, or “Old Woman”, the 150 or-more-long wall which surrounded most of the Bukhara Oasis and served as a bulwark against the hostile Turkish nomads who inhabited the deserts and steppes to the north. The invaders who would bring down Sogdiana and forever change the way of life in the Land Beyond the River came not from the north, however, but from the south, in form of Arabs who came proclaiming the new religion of Islam.

The Prophet Muhammed died in June of 632 a.d. Abu Bakr, his father-in-law and senior companion, assumed leadership of the Prophet’s followers and became the first of the Four Rightly Guided Caliphs. The Caliph and his successors had a simple mandate: the spread of Islam, by military conquest if necessary, to the far corners of the world. In the spring of 633 Arab General Khalid ibn Walid, acting under orders from Abu Bakr, invaded Mesopotamia (current-day Iraq), then part of the vast Sassanian Empire stretching from near the shores of the Mediterranean to the Indus River. The incursion faltered after the death of Abu Bakr in 1634, but under this successor the second Caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab the invasion continued and in September of 636 the Arabs defeated a huge Sassanian army in a three-day battle at the small town of Qadisiyyah, just east of Kufa and about one hundred miles southeast of Baghdad. Not long after the Sassanian imperial capital of Ctesiphon, eighteen miles southeast of Baghdad, surrendered without a fight, and the Sassanian emperor Yazdgird III along with his family and entourage fled eastward, taking refuge behind the natural border of the Zagros Mountains, which separated Mesopotamia from the Iranian Plateau. In 642 Caliph Umar ordered his Muslim armies over the Zagros Mountains into the Sassanian heartland. Although vastly outnumbered the Arabs soon scored a stunning victory at Nahāvand, about forty miles south of Hamadan in what is now Iran. The Battle of Nahāvand was a death blow to the Sassanians. According to Islamic historian al-Tabari (838–923), “from that day on, there was no further unity among them [the Persians] and the people of the individual provinces fought their own enemies on their own territory.”

Yazdgird III, accompanied by thousands of relatives, hangers-on, and a small contingent of still-loyal troops fled farther eastward to Khorasan, passing through Nishapur and finally reached the then-already ancient city of Merv (fifty-five miles northwest of Mary in current-day Turkmenistan). Envoys which he had dispatched to Sogdians and Turk tribesmen north of the Amu Darya and to the Tang Dynasty in China seeking aid to renew the battle against the Arabs came away empty-handed. Abandoned by the remainder of his troops, he again took flight and ended up hiding in the flour mill of a Christian miller on the banks of the Mugrab River south of Merv. In 651 he was assassinated, perhaps by the miller himself. After 427 years the Sassanian Empire was finally extinguished.

The same year Arab armies occupied Merv, 120 miles south of the Amu Darya, and Herat, on the western edge of Khorasan, and the following year Balkh, in Tokharistan (current day northern Afghanistan), just thirty-five miles south of the Amu Darya. The Arabs invaders, now colonists, set up a governorship in Merv and used it as a base for further military forays to the north. Small raiding parties operating out of Merv may have penetrated Khorezm on the lower Amu Darya in the 660s, but the first substantial campaign north of the Amu Darya took place in 673, when the governor of Khorasan Ubaidullah b. Ziyad led a force across the river to Bukhara. The Arabs were now in Transoxiania, or as they called it, Mawarannahr, literally “that which is beyond the river.”

At this time Bukhara was still a Sogdian city and according to some accounts it was ruled by a khatun, or queen, who was the mother of the young Tugshada, the nominal Bukhar Khudat (ruler of Bukhara). She negotiated a truce with the Arabs and after paying them tribute of a million dirhams and 4,000 slaves they retreated back south of the river.

For the next thirty years the Arabs continued to raid Bukhara and other cities in Mawarannahr and Khorezm but after demanding tribute from the local rulers, plundering the countryside, and enslaving Sogdians they continued to return to their bases south of the Amu Darya. In 705 al-Walid I ibn Abd al-Malik became the new Umayyads Caliph in Damascus, and under his reign the actual conquest of Mawarannahr began. Qutaiba b. Muslim, newly appointed governor of Khorasan, led an Arab army across the Amu Darya at Amul and in 706 attacked the city of Paikend at the very southern edge of the Bukhara Oasis.

After a two-month siege the city fell. Qutaiba left a small garrison of troops and returned to Merv, but soon after his departure the Arab troops were expelled from the city. Qutaiba returned and wrecked horrific revenge, putting the fighting men to death, enslaving the women, and completely plundering the city. Enormous amounts of booty was seized, including armor and weapons the quality of which amazed the Arabs. The message to the rest of the Zerafshan Valley was clear; submit and pay tribute or face annihilation.

With the destruction of Paikend the way was clear to Bukhara, thirty-one miles to the northeast. Assaults on Bukhara in 707 and 708 failed, but 709 Bukhara and several other cities in Mawarannahr finally surrendered to Qutaiba. From the Bukharans he collected tribute of 200,000 dirhams for the Caliph back in Damascus and 20,000 for the governor of Khorasan. A garrison was stationed in the city and every homeowner was made to house and presumably feed Arab troops.

In 712 Qutaiba built the first mosque in Bukhara on the former site of a temple in the Ark, marking the introduction of Islam into the city. The temple may be been Zoroastrian, or possible even Buddhist. Apparently the local people did not immediately accept Islam, since, according to tenth-century historian of Bukhara Narshakhi, Qutaiba had proclaimed, “Whoever is present at the Friday prayer, I will give two dirhams.” The Quran had to be read in Sogdian, since none of the local people understood Arabic.

For the next hundred years Arabs maintained tenuous control of Bukhara and other cities in Mawarannahr. Revolts by the indigenous Sogdians were frequent, and in 729 they succeeded in expelling the Arabs from Bukhara altogether, although the city was taken a few months later. In the 740s the Abbasids (descendants of Abbas, uncle of the Prophet Muhammad) attempted to seize control of the Islamic geo-sphere from the Umayyads. Their lieutenant in Khorasan and Mawarannahr, Abu Muslim, defeated the Umayyads in 747–748, and local people, believing they were being liberated, flocked to his banner. They soon realized, however, that the Abbasids, who finally seized the Caliphate in 750, were no better than the Umayyads. Revolts and rebellions against the ruling Arabs continued.

Monday, December 24, 2012

Tajikistan | More On Rudaki

Still trying to straighten out where 10th century Persian Poet Rudaki was born and buried. As noted earlier, a source in Samarkand indicated that he may have been born near the Town of Urgut in Uzbekistan, very close to the Tajikistan border. Most written sources indicate, however, that he was born and buried in the village of Panjrud (also spelled Panj Rud, Panjrudak, Panj Rudak, etc.) in Tajikistan. Traveler Nicholas Jubber was apparently in Panj Rud and in his book Drinking Arak Off An Ayatollah’s Beard says that Rudaki is buried there, but says nothing about where he was born. This Panj Rud is about twenty-six miles east-southeast of Panjkend, up the valley of a tributary of the Zerafshan River.

Map showing location of Panj Rud (click on image for enlargement)

This Site shows photos of what is apparently Panj Rud, although unfortunately there are no captions (photos below from the website).

Mountains looming above what is apparently the village of Panj Rud

Presumably the Mausoleum of Rudaki in Panj Rud

Presumably a statue of Rudaki in Panj Rud

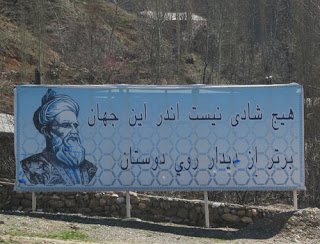

A billboard in Panj Rud with what is presumably an example of Rudaki’s poetry. It reads “There is no happiness in this world greater than a glimpse of a friend’s face”. Thanks to Abbas Daiyar for the translation.)

There is also a monument and statue to Rudaki in Dushanbe, the capital of Tajikistan.

I have never been in Tajikistan, but the last time I was in Samarkand I was told that tourist agencies there could get a one-day Tajikistan visa for people who want to visit the famous ruins of Panjakend, thirty-seven miles east of Samarkand and eleven miles within Tajikistan. They also arrange for you to get back into Uzbekistan at the end of the day if you have only a single-entry Uzbek visa. Presumably one could also visit Panj Rud in one day also. I might just try this the next time I am in Samarkand.

Tajikistan | More On Rudaki

Still trying to straighten out where 10th century Persian Poet Rudaki was born and buried. As noted earlier, a source in Samarkand indicated that he may have been born near the Town of Urgut in Uzbekistan, very close to the Tajikistan border. Most written sources indicate, however, that he was born and buried in the village of Panjrud (also spelled Panj Rud, Panjrudak, Panj Rudak, etc.) in Tajikistan. Traveler Nicholas Jubber was apparently in Panj Rud and in his book Drinking Arak Off An Ayatollah’s Beard says that Rudaki is buried there, but says nothing about where he was born. This Panj Rud is about twenty-six miles east-southeast of Panjkend, up the valley of a tributary of the Zerafshan River.

Map showing location of Panj Rud (click on image for enlargement)

This Site shows photos of what is apparently Panj Rud, although unfortunately there are no captions (photos below from the website).

Mountains looming above what is apparently the village of Panj Rud

Presumably the Mausoleum of Rudaki in Panj Rud

Presumably a statue of Rudaki in Panj Rud

A billboard in Panj Rud with what is presumably an example of Rudaki’s poetry. It reads “There is no happiness in this world greater than a glimpse of a friend’s face”. Thanks to Abbas Daiyar for the translation.)

There is also a monument and statue to Rudaki in Dushanbe, the capital of Tajikistan.

I have never been in Tajikistan, but the last time I was in Samarkand I was told that tourist agencies there could get a one-day Tajikistan visa for people who want to visit the famous ruins of Panjakend, thirty-seven miles east of Samarkand and eleven miles within Tajikistan. They also arrange for you to get back into Uzbekistan at the end of the day if you have only a single-entry Uzbek visa. Presumably one could also visit Panj Rud in one day also. I might just try this the next time I am in Samarkand.

Friday, December 21, 2012

Mongolia | Zaisan Tolgoi | Weather Update

Update From Yesterday: The temperature at 8:30 AM was 36º below 0 F, maybe cold enough to freeze twice-distilled arkhi. This is not supposed to happen until the Second Nine-Nine, so we seem to be having unseasonably cold weather. Last year the low for this date was 23º below 0 F. And the forecast for tonight is 44º below zero. Remember, 40º below is the Magical Moment when the Fahrenheit and Celsius scales coincide. This is the first time in my more than ten winters in Ulaanbaatar that I can recall the Magical Moment occurring in December.

Latest Update: We did not have to wait for tonight. We reached the Magical Moment at 9:25 this morning. Usually the temperature does not continue to drop after the sun comes up. It did this morning.

Latest Update: We did not have to wait for tonight. We reached the Magical Moment at 9:25 this morning. Usually the temperature does not continue to drop after the sun comes up. It did this morning.

Mongolia | Zaisan Tolgoi | Weather Update

Update From Yesterday: The temperature at 8:30 AM was 36º below 0 F, maybe cold enough to freeze twice-distilled arkhi. This is not supposed to happen until the Second Nine-Nine, so we seem to be having unseasonably cold weather. Last year the low for this date was 23º below 0 F. And the forecast for tonight is 44º below zero. Remember, 40º below is the Magical Moment when the Fahrenheit and Celsius scales coincide. This is the first time in my more than ten winters in Ulaanbaatar that I can recall the Magical Moment occurring in December.

Latest Update: We did not have to wait for tonight. We reached the Magical Moment at 9:25 this morning. Usually the temperature does not continue to drop after the sun comes up. It did this morning.

Thursday, December 20, 2012

Mongolia | Zaisan Tolgoi | Winter Solstice | First of the Nine Nines | Nermel Arkhi Khöldönö

The Winter Solstice occurs today, December 21, at 7:12 PM (Ulaanbaatar Time), marking the Beginning Of Winter.

Yesterday, December 20, the sun rose at 8:39 AM and set at 5:02 PM for a day of 8 hours, 22 minutes, and 59 seconds.

Today, the day of the Solstice, the sun rises at 8:39 AM and sets at 5:02 for a day of 8 hours, 22 minutes and 55 seconds, or four seconds shorter than the day before.

Tomorrow, December 22, the day after the Solstice, the sun will rise at 8:40 PM and set at 5:03 PM for a day of 8 hours, 22 minutes, and 56 seconds, one second longer than the previous day. So the days will be getting longer . . .

In Mongolia the Winter Solstice also marks the beginning of the so-called Nine-Nines: nine periods of nine days each, each period marked by some description of winter weather. The first of the nine nine-day periods is Nermel Arkhi Khöldönö, the time when once-distilled homemade Mongolian arkhi (vodka) freezes. It was minus 35º F. at 9:30 a.m., cold enough, I think, to freeze Mongolian moonshine, which is not as strong as the store-bought vodka. The Second Nine-Day Period starts on December 30. Stayed tuned for updates.

As you all know, Venus has been dominating the dawn skies for the last couple weeks, but this morning also offers an excellent opportunity to see the elusive plant Mercury. Pull on your mukluks and get out there! You do not want to miss this!

As usual, Neo-Druids and others are whooping it up at Stonehenge, the granddaddy of all Solstice Celebration sites.

Neo-Druids at Stonehenge

Neo-Druids at Stonehenge

Neo-Druids at Stonehenge

See More Stonehenge Photos (click on photo for enlargement)

Winter Solstice Offering

Mongolia | Zaisan Tolgoi | Winter Solstice | First of the Nine Nines | Nermel Arkhi Khöldönö

The Winter Solstice occurs today, December 21, at 7:12 PM (Ulaanbaatar Time), marking the Beginning Of Winter.

Yesterday, December 20, the sun rose at 8:39 AM and set at 5:02 PM for a day of 8 hours, 22 minutes, and 59 seconds.

Today, the day of the Solstice, the sun rises at 8:39 AM and sets at 5:02 for a day of 8 hours, 22 minutes and 55 seconds, or four seconds shorter than the day before.

Tomorrow, December 22, the day after the Solstice, the sun will rise at 8:40 PM and set at 5:03 PM for a day of 8 hours, 22 minutes, and 56 seconds, one second longer than the previous day. So the days will be getting longer . . .

In Mongolia the Winter Solstice also marks the beginning of the so-called Nine-Nines: nine periods of nine days each, each period marked by some description of winter weather. The first of the nine nine-day periods is Nermel Arkhi Khöldönö, the time when once-distilled homemade Mongolian arkhi (vodka) freezes. It was minus 35º F. at 9:30 a.m., cold enough, I think, to freeze Mongolian moonshine, which is not as strong as the store-bought vodka. The Second Nine-Day Period starts on December 30. Stayed tuned for updates.

As you all know, Venus has been dominating the dawn skies for the last couple weeks, but this morning also offers an excellent opportunity to see the elusive plant Mercury. Pull on your mukluks and get out there! You do not want to miss this!

As usual, Neo-Druids and others are whooping it up at Stonehenge, the granddaddy of all Solstice Celebration sites.

Neo-Druids at Stonehenge

Neo-Druids at Stonehenge

Neo-Druids at Stonehenge

Winter Solstice Offering

Wednesday, December 12, 2012

Uzbekistan | Tajikistan | Birthplace of Rudaki

The dispute over the birthplace of the Poet Rudaki (858–c.941) is heating up and may soon lead to wine-throwing and fist-fights among enthusiasts of tenth-century Persian poetry. It appears that both Uzbekistan and Tajikistan are claiming Rudaki as one of their own. According to some sources Rudaki (or Rudagi, as it is often rendered in English) was born in the village of Rudak, sometimes called Panjrudak. This village does not show up on any available maps, but it is said to be near Urgut, twenty miles southwest of Panjakend, or twenty-three miles southeast of Samarkand. Urgut, however, is in Uzbekistan, seven miles from the Uzbek-Tajik border. Since Rudak or Panjrudak is described only as “near” Urgut, it could be across the border in Tajikistan.

Places connected with Rudaki. The Uzbek-Tajik border is in yellow (click on image for enlargement).

Others, however, including some people in Tajikistan, insist that he was born in a small village on the upper reaches of the Kshtut River. There is a place named Kshtut 47 miles south of Panjakend, in Uzbekistan, just fifteen miles west of the border. This is an extremely mountainous area. Right on the border here is the highest point in Uzbekistan, 15,233-foot Khazret Sultan Mountain. Whether this is the Kshtut referred to by my informants I cannot say.

Other people claim that his name Rudaki, or Rudagi, comes not from his village, but from the name of a musical instrument known as the “rood”, which Rudaki played to perfection. But then in certain Tajik dialects “roodek” is said to mean “blind”, and thus the poet’s name may refer to his alleged blindness and not to the village where he was born. So the origins of the poet’s name are not so clear-cut after all. Anyone who has any more information on this subject please feel free to weigh in. But please, no wine-tossing. Wine is too valuable to waste. As Rudaki himself said:

Were there no wine all hearts would be a desert waste, forlorn and black,

But were our last life-breath extinct, the sight of wine would bring it back.

A modern-day version of the instrument known as a “rood”.

Monday, December 10, 2012

Uzbekistan | Bukhara | al-Bukhari | Narshakhi | Ibn Sina

The Persian Historian Juvaini (1226–1283) could barely contain himself when hymning Bukhara:

In the eastern countries it is the cupola of Islam and is in those regions like unto the City of Peace. Its environs are adorned with the brightness of the light of doctors and jurists and its surroundings embellished with the rarest of high attainments. Since ancient times it has in every age been the place of assembly of the great savants of every religion.

It was just before and during the Samanid Era that an array of religious scholars, philosophers, poets, historians, and writers first lit up the sky over Bukhara with their brilliance. The era was kicked off by Muhammad ibn Ismail al-Bukhari (d.870), who according to most accounts was born near Samarkand. He traveled widely as a youth and young man, making a pilgrimage to Mecca as a teenager, but then settled down in Bukhara and wrote his Sahih al-Bukhari, a compendium of hadith, or sayings attributed to the Prophet Muhammad. He reported winnowed through more than 600,000 hadith before selecting 7,275 for inclusion in his collection. His Sahih was eventually recognized as one of six canonical collections of hadith accepted among Sunnis and in the opinion of some one of the two most important. The Sahih al-Bukhari is widely read to this day, and al-Bukhari’s mausoleum near Samarkand is now visited by pilgrims from throughout the Islamic geo-sphere.

Mausoleum Complex of al-Bukhari near Samarkand (click on photos for enlargements)

Mausoleum of al-Bukhari

Mausoleum of al-Bukhari

Tomb of al-Bukhari

Tomb of al-Bukhari

Al-Bukhari died just as the Samanids were ascending to power, but the afterglow of his work would add luster to the new regime. Historians were represented by Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Jafar Narshakhi (ca. 899–959), from the village of Narshak in the Bukhara Oasis. His History of Bukhara offers a unique view of both pre-Samanid Sogdiana and the Bukhara Oasis during the reign of the Samanids. The book, originally written in Arabic, was present to his patron the Samanid emir Nuh ibn Nasr in the 940s. It was translated into Persian 1034 and translations into English remain in print to this day. A Russian language scholarly edition with extensive commentary was published in 2011.

Bukhara’s intellectual lustre, burnished by local talent, soon attracted the leading lights from throughout the Islamic geosphere. This concentration of scholarly and artistic firepower led to the creation of the Siwan-al-hikma (Storehouse of Wisdom), a library which soon boasted of one of the best collections in Inner Asia if not the world. Apart from the library, the Bukhara book bazaar achieved fame among bibliomanes as a place where books on even the most recondite and esoteric subjects could be found for sale.

It was in Bukhara’s libraries and well-stocked book stalls that the towering intellectual figure who bookended the Samanid era found his early sustenance. This was Abu Ali Ibn Sina, born in the village of Afsana just outside of Bukhara in 980, two decades before the fall of the Samanids. A scientist, philosopher, physician, mathematician, poet, and belletrist, the polymathic Ibn Sina (better known in English language literature as Avicenna) was, and is, widely recognized as the greatest Islamic scholar of the Middle Ages. “At the age of ten years,” the twelfth-century biographer of poets Ibn Khallikan (1211–1282) tells us, “he had mastered the Koran and general literature and had obtained a certain degree of information in dogmatic theology, the Indian calculus . . . and algebra.”

Ibn Sina then applied himself to further studies in logic, natural science, the mystical teachings of the Sufis, astronomy, medicine, and a potpourri of other subjects. His progress in medicine was so phenomenal that at the age of seventeen he was treating Nuh b. Mansur, one of the last Samanid emirs. It was this prince who allowed Ibn Sina to use his library (this may have been the Siwan-al-hikma mentioned above, or the ruler’s own library; the record is unclear). Here, Ibn Sina tells us, he found “many books the very titles of which were unknown to most persons, and others which I have not met with before or since.”

Unfortunately for Ibn Sina, the Samanid empire fell before he turned twenty, and he was forced to spend the rest of his life as a exile in courts of various potentates in Khorasan and Iraq-Ajami who were only too happy finance his intellectual endeavors as long as he keep his nose in his books and did not cause any trouble. Life was not easy—he was thrown in prison at least once and threatened with execution for rattling the chains of his patrons—but he was able to produce an immense corpus of work numbering almost a hundred volumes. He died in Isfahan, in Iraq-Ajami (modern western Iran), in 1037. Two of his most famous books, The Metaphysics of Healing and the Canon of Medicine, remain in print in modern editions to this day (both get five-star ratings on Amazon), and his birthplace at Afsana, on the outskirts of Bukhara, is a much frequented tourist and pilgrimage attraction with a medical school, a museum devoted to Ibn Sina, and breathtakingly gorgeous rose gardens.

Statue of Ibn Sina (Avicenna) at the Ibn Sina Museum near Afsana, on the outskirts of Bukhara

Grounds at the Ibn Sina Complex

Breathtakingly gorgeous roses at the Ibn Sina Complex

Another example of a breathtakingly gorgeous rose.

Uzbekistan | Bukhara | al-Bukhari | Narshakhi | Ibn Sina

The Persian Historian Juvaini (1226–1283) could barely contain himself when hymning Bukhara:

In the eastern countries it is the cupola of Islam and is in those regions like unto the City of Peace. Its environs are adorned with the brightness of the light of doctors and jurists and its surroundings embellished with the rarest of high attainments. Since ancient times it has in every age been the place of assembly of the great savants of every religion.

It was just before and during the Samanid Era that an array of religious scholars, philosophers, poets, historians, and writers first lit up the sky over Bukhara with their brilliance. The era was kicked off by Muhammad ibn Ismail al-Bukhari (d.870), who according to most accounts was born near Samarkand. He traveled widely as a youth and young man, making a pilgrimage to Mecca as a teenager, but then settled down in Bukhara and wrote his Sahih al-Bukhari, a compendium of hadith, or sayings attributed to the Prophet Muhammad. He reported winnowed through more than 600,000 hadith before selecting 7,275 for inclusion in his collection. His Sahih was eventually recognized as one of six canonical collections of hadith accepted among Sunnis and in the opinion of some one of the two most important. The Sahih al-Bukhari is widely read to this day, and al-Bukhari’s mausoleum near Samarkand is now visited by pilgrims from throughout the Islamic geo-sphere.

Mausoleum Complex of al-Bukhari near Samarkand (click on photos for enlargements)

Mausoleum of al-Bukhari

Mausoleum of al-Bukhari

Tomb of al-Bukhari

Tomb of al-Bukhari

Al-Bukhari died just as the Samanids were ascending to power, but the afterglow of his work would add luster to the new regime. Historians were represented by Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Jafar Narshakhi (ca. 899–959), from the village of Narshak in the Bukhara Oasis. His History of Bukhara offers a unique view of both pre-Samanid Sogdiana and the Bukhara Oasis during the reign of the Samanids. The book, originally written in Arabic, was present to his patron the Samanid emir Nuh ibn Nasr in the 940s. It was translated into Persian 1034 and translations into English remain in print to this day. A Russian language scholarly edition with extensive commentary was published in 2011.

Bukhara’s intellectual lustre, burnished by local talent, soon attracted the leading lights from throughout the Islamic geosphere. This concentration of scholarly and artistic firepower led to the creation of the Siwan-al-hikma (Storehouse of Wisdom), a library which soon boasted of one of the best collections in Inner Asia if not the world. Apart from the library, the Bukhara book bazaar achieved fame among bibliomanes as a place where books on even the most recondite and esoteric subjects could be found for sale.

It was in Bukhara’s libraries and well-stocked book stalls that the towering intellectual figure who bookended the Samanid era found his early sustenance. This was Abu Ali Ibn Sina, born in the village of Afsana just outside of Bukhara in 980, two decades before the fall of the Samanids. A scientist, philosopher, physician, mathematician, poet, and belletrist, the polymathic Ibn Sina (better known in English language literature as Avicenna) was, and is, widely recognized as the greatest Islamic scholar of the Middle Ages. “At the age of ten years,” the twelfth-century biographer of poets Ibn Khallikan (1211–1282) tells us, “he had mastered the Koran and general literature and had obtained a certain degree of information in dogmatic theology, the Indian calculus . . . and algebra.”

Ibn Sina then applied himself to further studies in logic, natural science, the mystical teachings of the Sufis, astronomy, medicine, and a potpourri of other subjects. His progress in medicine was so phenomenal that at the age of seventeen he was treating Nuh b. Mansur, one of the last Samanid emirs. It was this prince who allowed Ibn Sina to use his library (this may have been the Siwan-al-hikma mentioned above, or the ruler’s own library; the record is unclear). Here, Ibn Sina tells us, he found “many books the very titles of which were unknown to most persons, and others which I have not met with before or since.”

Unfortunately for Ibn Sina, the Samanid empire fell before he turned twenty, and he was forced to spend the rest of his life as a exile in courts of various potentates in Khorasan and Iraq-Ajami who were only too happy finance his intellectual endeavors as long as he keep his nose in his books and did not cause any trouble. Life was not easy—he was thrown in prison at least once and threatened with execution for rattling the chains of his patrons—but he was able to produce an immense corpus of work numbering almost a hundred volumes. He died in Isfahan, in Iraq-Ajami (modern western Iran), in 1037. Two of his most famous books, The Metaphysics of Healing and the Canon of Medicine, remain in print in modern editions to this day (both get five-star ratings on Amazon), and his birthplace at Afsana, on the outskirts of Bukhara, is a much frequented tourist and pilgrimage attraction with a medical school, a museum devoted to Ibn Sina, and breathtakingly gorgeous rose gardens.

Statue of Ibn Sina (Avicenna) at the Ibn Sina Museum near Afsana, on the outskirts of Bukhara

Grounds at the Ibn Sina Complex

Breathtakingly gorgeous roses at the Ibn Sina Complex

Another example of a breathtakingly gorgeous rose.

Sunday, December 9, 2012

Uzbekistan | Bukhara | Magok-i Attari

Bukhara claims to be one of the world’s oldest cities. In 1997 the city celebrated its 2500th anniversary, although admittedly this date seems to have been chosen somewhat arbitrarily. According to archeological findings, the earliest levels of settlement in Bukhara date from somewhere between the fifth and second centuries b.c. A “large, sprawling settlement” and earliest manifestation of the Ark (Citadel) appear somewhere in this time frame. Whether they existed by the time Alexander The Great And The Greeks Swept Through The Region is unclear. An ark did soon appear however (apparently on roughly the same spot as the current-day Citadel). and by the third century b.c. it had been re-enforced with walls over twenty feet thick.

The current-day Ark is a much later structure, but it supposedly stands on the same site as the ancient arks of 2300 or so years ago. (Click on photos for Enlargements)

At this time the Bukhara Oasis was part of the Bactrian Kingdom founded by the descendants of the Greek adventurer and centered around the city of Balkh (Bactria) in the current-day country of Afghanistan. In the second century b.c. nomads from the east known as the Yuezhi (also “Yüeh-chih”) occupied the land between the rivers. Later they expanded south of the Amu Darya and eventually established the Kushan Empire, from the first through fourth centuries a.d. a principal power in Inner Asia and what is now Afghanistan. Coterminous with India, the Kushan Empire was heavily influenced with Buddhism. Many Buddhist texts were translated into the Kushan language and from the Kushan into Sogdian and Chinese. Under the Kushans the first through fourth centuries a.d. Buddhism was introduced into the land between the rivers, although to what degree it flourished is unclear.

Archeological evidence suggests that the former Magok-i Attari Mosque in Bukhara may have been built on the site of a Buddhist monastery during the Kushan era. Magok-i-Attari, or Maghak-i Attari, means “scented pit” according to some renderings, or the “moque in the pit” according to others. The first rendering may refer to the aromatic herb markets once found in the area. Both renderings refer to the structure’s sunken structure, the base of which was lower than the surrounding area even in Sogdian days. Today the building remains in a sunken area approached from all directions by steps. The lowest levels of the structure date to at least as far back as the fifth century and maybe much further. The early use of the building is veiled in mystery, but it have have first been a Zoroastrian temple and later a Buddhist temple, or vice-versa. It or a adjacent structure, now missing, may also have been a temple to Moh, the lunar deity beloved by moon worshippers, myself included. Apparently it was converted to a mosque soon after the Arab invasion of Bukhara in the early eighth century. Nothing now remains of this early mosque. The southern portal, now the best restored part of the building, was built in the twelfth century by the Qarakhanids, who also built the Rabat-i-Malik, an immense caravanserai for the use of merchants and travelers on the Royal Road from Bukhara to Samarkand, and the Kalon Minaret. The Ashtarkanid ruler Abdulaziz Khan (r. 1645–1681), who also built the Abdulaziz Madrassa, updated the building to approximately its current configuration in 1546-47. The eastern portal is a twentieth century addition and clearly the production of a much more mundane era. The building now serves as a carpet museum.

Magok-i Attari. As can be seen, it is now ten or more feet lower than the surrounding area.

The southern facade, added by the Qarakhanids in the twelfth century, with probably more additions by Abdulaziz Khan in the seventeenth.

Portal on the southern facade

Details of the southern facade

Details of the southern facade

Details of the southern facade. The insert ornaments are thought to be Zoroastrian symbols. They were frequently incorporated in the designs of mosques and Other Islamic Buildings.

Details of the southern facade

Details of the southern facade

Inside the building is a archeological digging which reportedly goes down to the Zoroastrian and/or Buddhism levels of the building.

I drooled over carpets now on display in the museum.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Italy | Venice | Early Life of Enrico Dandolo

There are few greater ironies in History than the fact that the fate of Eastern Christendom should have been sealed—and half of Europe conde...

-

The city of Midyat, about thirty-seven miles east-northeast of Mardin , is in the middle of Tur Abdin , the old Syriac Christian heartland ...

-

The largely Kurdish city of Nusaybin is located twenty-four miles south of Midyat , on the southern edge of the mountainous plateau known as...

-

Update : Mormons have now jumped on the eschatological bandwagon: “They predict the full moon Sept. 28 is the next sign the world is ending....